In the summer of 2016, after doing a little research on my family tree, I traveled to Dromahair, Ireland, to see the place where my great-grandfather, Martin Smith, was born and raised. He emigrated to the States as a young man; my nana said he got involved with the local IRB, and his parents sent him to America because they didn’t want him getting into trouble.

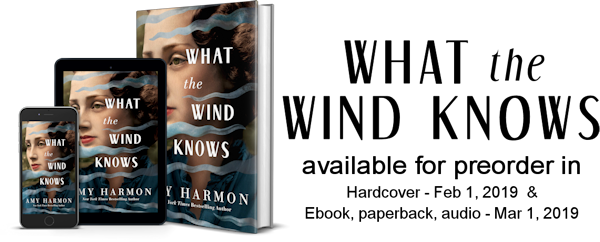

I don’t know if that’s true, as Nana has been gone since 2001, but he was born the same year as Michael Collins, in a period of reformation and revolution. Nana had written a few things on the back of a St. Patrick’s Day card one year about her father, my great-grandfather. I knew when he was born, I knew his mother’s name was Anne Gallagher, and his father was Michael Smith. But that’s all I knew. Just like the main character in What The Wind Knows, I went to Dromahair with the hopes of finding them. And I did.

My parents and my older sister took the trip with me, and the first time we saw Lough Gill, my chest burned, and my eyes teared. Every step of the way, it felt like we were being guided and led. Deirdre Fallon, a real-life librarian—libraries never let you down—in Dromahair directed us to the genealogical center in Ballinamore. We were then directed to Ballinagar, a cemetery behind a church in the middle of fields. When I asked how we would find it, I really was told to pray or pull over and ask someone, just like Anne was told to do in this book. I won’t ever forget how it felt to walk up that rise among the stones and find my family.

I couldn’t give my main character my great-great grandfather’s name (Michael Smith) because Michael Collins was such a central figure in the book, and I didn’t want two Michaels. So Thomas Smith was named for two of my Irish grandfathers, Thomas Keefe of Youghal, County Cork, and Michael Smith of Dromahair, County Leitrim. We also have a Bannon branch that I can’t get a lock on. Maybe there will be another book about John Bannon.

Even though this book has a strong dose of the fantastical, I wanted it to be a historical novel as well. The more research I did into Ireland, the more lost I felt. I didn’t know how to tell the story or even what story to tell. I felt like Anne when she told Eoin, “There is no consensus. I have to have context.” It was Eoin’s response to Anne, “Don’t let the history distract you from the people who lived it,” that gave me hope and direction.

Ireland’s history is a long and tumultuous one, and I did not wish to relitigate it or point fingers of blame in this story. I simply wanted to learn, understand, and fall in love with her and invite my reader to love her too. In the process, I immersed myself in the poetry of Yeats, who walked the streets my great-grandfather walked and who wrote about Dromahair. I also fell in love with Michael Collins.

If you want to know more about him, I highly suggest Tim Pat Coogan’s book, Michael Collins, to gain a deeper appreciation of his life and his place in Irish history. There is so much written about him, and so many opinions, but after all my research, I am still in awe of the young man who committed himself, heart and soul, to his cause. That much is not in dispute. Of course, Thomas Smith is a fictional character, but I think he embodies the kind of friendship and loyalty Michael Collins inspired among those who knew him. I did my best to blend fact and fiction, and many of the events and accounts I inserted Thomas and Anne into actually happened.

Any mistakes or embellishments to the actual record to fill in the historical gaps or to further the story are well intentioned and are completely my own. I only hope when you are finished with What the Wind Knows, you have a greater respect for the men and women who came before and a desire to make the world a better place.